Reader, you may call what you see here my blog, but the truth is that what I create here is not a blog, not exactly. It’s rather my ruminations and conversations, which are lively, kindly even in their silliness, and which are built always upon the bedrock of my devotion to the written word as it expands, as it is lit by my unguarded honesty. I have not written here out of imagination and invention, but out of meditation on what I read and what relates to the experiences of my own life, illuminated by the path made by living rather than planning.

Reader, you may call what you see here my blog, but the truth is that what I create here is not a blog, not exactly. It’s rather my ruminations and conversations, which are lively, kindly even in their silliness, and which are built always upon the bedrock of my devotion to the written word as it expands, as it is lit by my unguarded honesty. I have not written here out of imagination and invention, but out of meditation on what I read and what relates to the experiences of my own life, illuminated by the path made by living rather than planning.

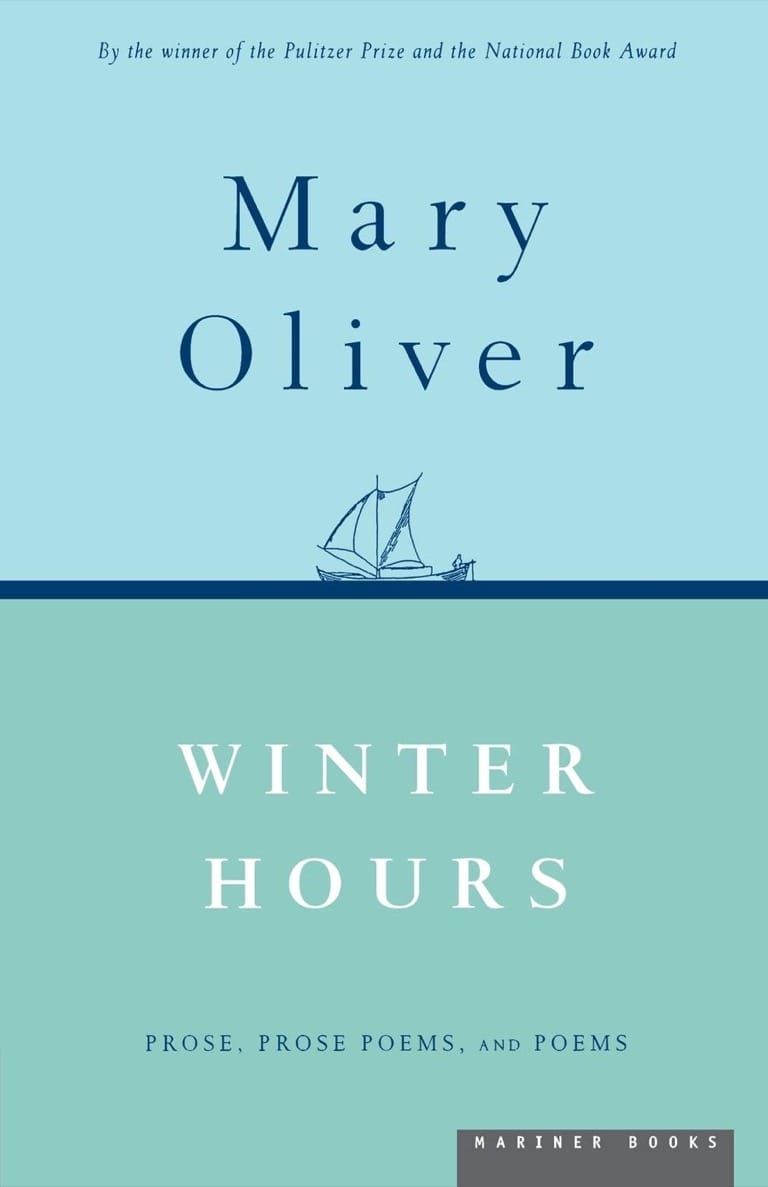

So what you’ll find here is a house I built out of words, words selected and sourced by the process of pure curiosity and reverence for life in all its mystery and wonder. This is a house filled with conversations and letters which I send to you, and which become a part of your own house, both physical and metaphysical. As you lay down the foundation, build, and rebuild the dwelling place of your body and mind, you can’t help but notice a subtle interplay of the conscious and subconscious that fill the blueprint of your life. This delicate weaving of seen and unseen, the dreamer and the dreamed, is one of many questions the beloved poet Mary Oliver (September 10, 1935–January 17, 2019) explores in her essay “Building the House” included in the meditative Winter Hours.

Houses built of words, thoughts, and dreams — more than houses built of bricks and stones — can serve as a measure of a life well lived, a life examined. Mary Oliver writes:

Whatever a house is to the heart and body of man — refuge, comfort, luxury — surely it is as much or more to the spirit. Think how often our dreams take place inside the houses of our imaginations! Sometimes these are fearful, gloomy, enclosed places. At other times they are bright and have many windows and are surrounded by gardens combed and invitational, or unpathed and wild. Surely such houses appearing in our sleep-work represent the state of the soul, or, if you prefer it, the state of the mind. Real estate, in any case, is not the issue of dreams.

The condition of our true and private self is what dreams are about. If you rise refreshed from a dream — a night’s settlement inside some house that has filled you with pleasure — you are doing okay. If you wake to the memory of squeezing confinement, rooms without air or light, a door difficult or impossible to open, a troubling disorganization or even wreckage inside, you are in trouble — with yourself. There are houses that pin themselves upon the windy porches of mountains, that open their own windows and summon in flocks of wild and colorful birds — and there are houses that hunker upon narrow ice floes adrift upon endless, dark waters; houses that creak, houses that sing; houses that will say nothing at all to you though you beg and plead all night for some answer to your vexing questions.

But houses built of bricks and stones, houses worth living in, can only spring out of a mind clear of inner turmoil and conflict. Mary Oliver writes:

As such houses in dreams are mirrors of the mind or the soul, so an actual house, such as I began to build, is at least a little of that inner state made manifest. Jung, in a difficult time, slowly built a stone garden and a stone tower. Thoreau’s house at Walden Pond, ten feet by fifteen feet under the tall, arrowy pines, was surely a dream-shape come to life. For anyone, stepping away from actions where one knows one’s measure is good. It shakes away an excess of seriousness.

Building my house, or anything else, I always felt myself becoming, in an almost devotional sense, passive, and willing to play. Play is never far from the impress of the creative drive, never far from the happiness of discovery. Building my house, I was joyous all day long. … When my house was finished, my friend Stanley Kunitz gave me a yellow door, discarded from his house at the other end of town. Inside, I tacked up a van Gogh landscape, a Blake poem, a photograph of Mahler, a picture M. had made with colored chalk. Some birds’ nests hung in the corners. I lit the lamp. I was done.

Essential and necessary, Mary Oliver’s prose, prose poems, and poems will warm you during these long Winter Hours.