“Terrified of being alone, yet afraid of intimacy, we experience widespread feelings of emptiness, of disconnection, of the unreality of self,” Sherry Turkle wrote while reflecting on how computers affect our awareness of ourselves, of one another, and of our relationship with the world. “And here the computer, a companion without emotional demands, offers a compromise. You can be a loner, but never alone. You can interact, but need never feel vulnerable to another person.”

“Terrified of being alone, yet afraid of intimacy, we experience widespread feelings of emptiness, of disconnection, of the unreality of self,” Sherry Turkle wrote while reflecting on how computers affect our awareness of ourselves, of one another, and of our relationship with the world. “And here the computer, a companion without emotional demands, offers a compromise. You can be a loner, but never alone. You can interact, but need never feel vulnerable to another person.”

When the tragic events of 2020 forced everyone around the world to stay home, our computers were the only safe window to the outside world, our ways of connecting to friends, family, and loved ones. And even though we’re now in the process of slow recovery and human contact is not limited to digital screens and video calls, the issue of our excessive use of technology is not going away but might be more pressing than ever before. We should always re-examine our increasing reliance on computers and gadgets that have become an indispensable part of everyday life.

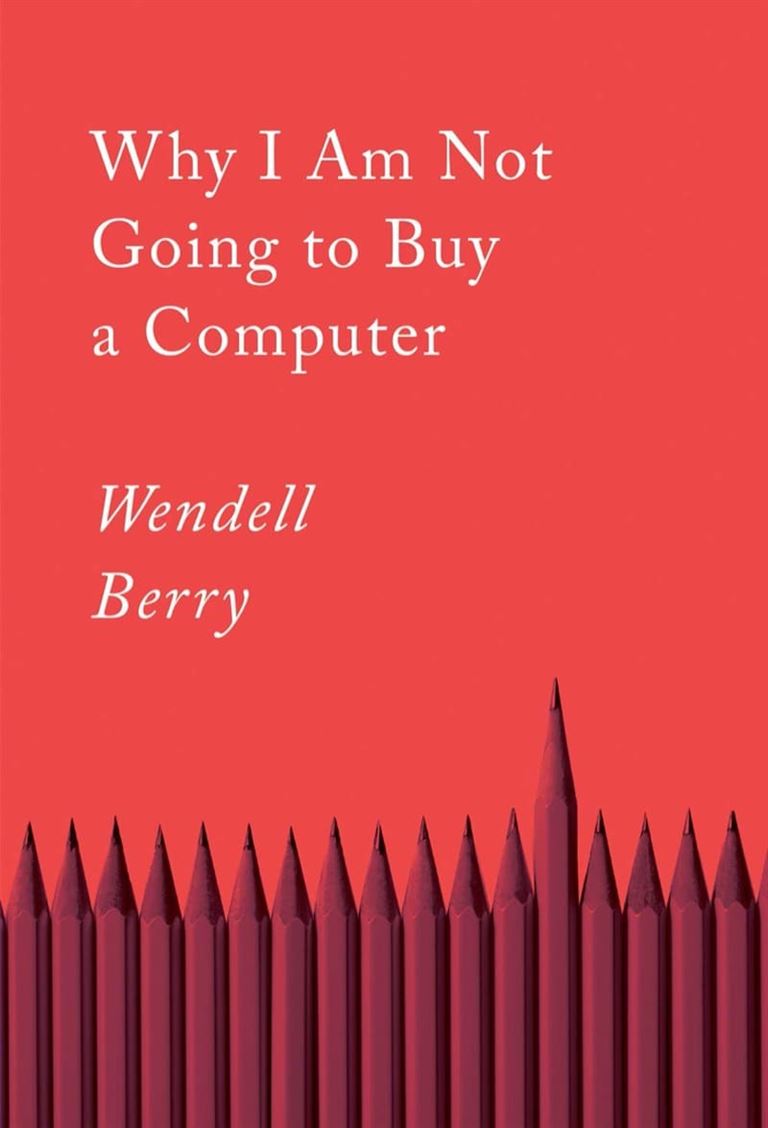

Wendell Berry (b. August 5, 1934), an American writer, poet, farmer, and devoted nature conservationist, offers us a refreshing view on this issue in his 1987 essay titled “Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer“, which still resonates with the same force as it did three decades ago. It offers us a perspective that challenges technological fundamentalism so prevalent in our digital age.

At the beginning of his essay, Wendell Berry writes that several people told him he could greatly improve things by buying a computer. But for him, it’s out of the question, and he gives several reasons for why it is so. The first one is that using a computer is the same as being dependent on strip-mined coal and energy corporations that are involved in the active destruction of nature. Berry writes:

I do not see that computers are bringing us one step nearer to anything that does matter to me: peace, economic justice, ecological health, political honesty, family and community stability, good work.

Another reason, Wendell Berry points out, is that he doesn’t believe that computer, as opposed to pen and paper, can make anyone’s writing better:

When somebody has used a computer to write work that is demonstrably better than Dante’s, and when this better is demonstrably attributable to the use of a computer, then I will speak of computers with a more respectful tone of voice, though I still will not buy one.

If a computer were to replace pen and paper, then it would have to adhere to a different set of innovation standards. Wendell Berry writes:

1. The new tool should be cheaper than the one it replaces.

2. It should be at least as small in scale as the one it replaces.

3. It should do work that is clearly and demonstrably better than the one it replaces.

4. It should use less energy than the one it replaces.

5. If possible, it should use some form of solar energy, such as that of the body.

6. It should be repairable by a person of ordinary intelligence, provided that he or she has the necessary tools.

7. It should be purchasable and repairable as near to home as possible.

8. It should come from a small, privately owned shop or store that will take it back for maintenance and repair.

9. It should not replace or disrupt anything good that already exists, and this includes family and community relationships.

“Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer,” an illuminating read for our technology-obsessed generation, sparked much controversy at the time of its publishing and includes five letters of criticism and Berry’s ingenious responses to those letters. Also included is his follow-up essay expanding on many of his original points titled “Feminism, the Body, and the Machine.” Complement with Sherry Turkle on the human spirit in a computer culture.

I’m a freelance writer with 6 years of experience in SEO blogging and article publishing. I currently run two websites: MindfulSpot.com and OurReadingLife.com. While you’re here, get the latest updates by subscribing to my newsletter.