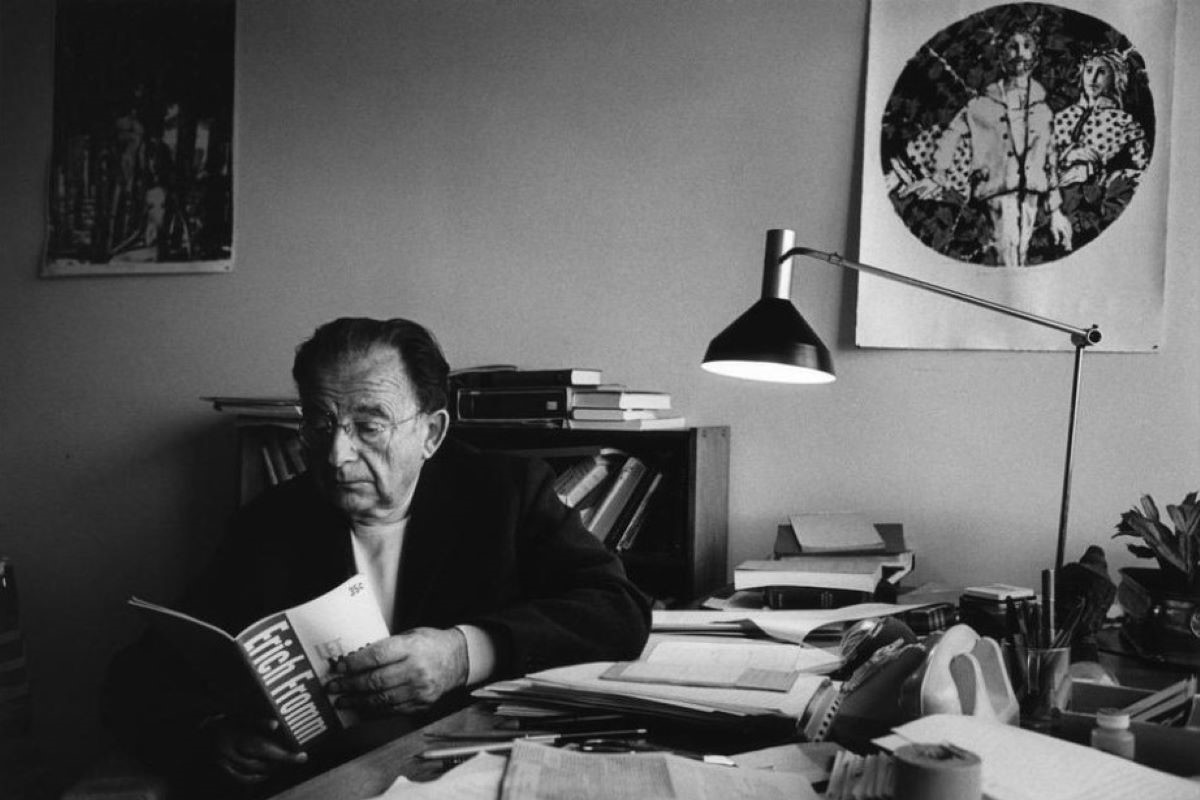

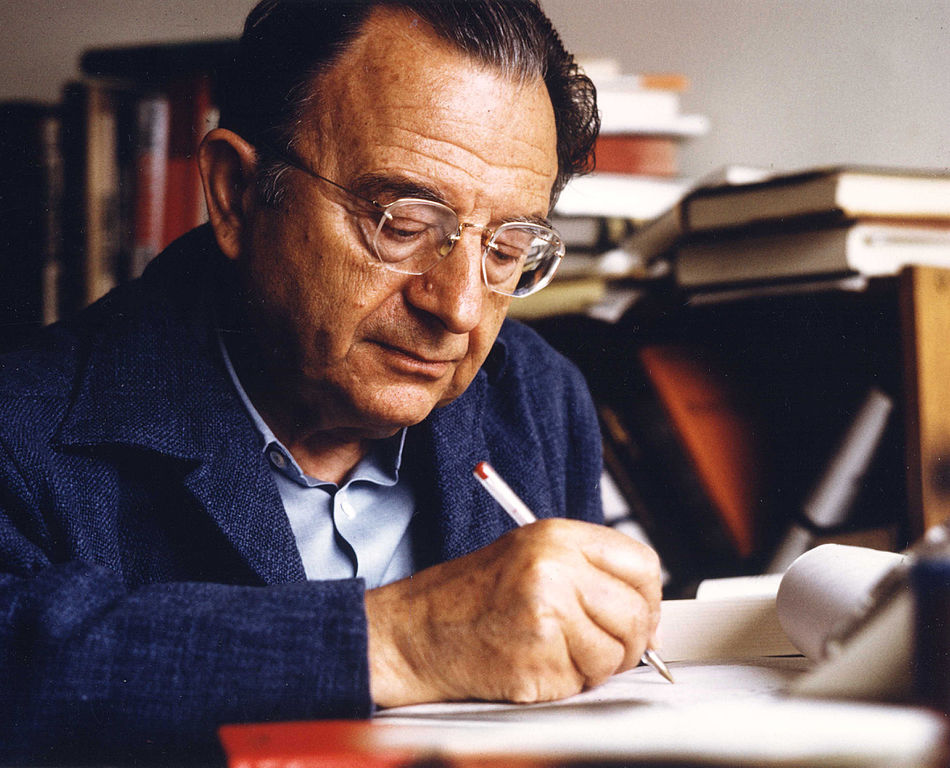

The renowned German psychologist and philosopher, Erich Fromm (March 23, 1900–March 18, 1980), explored a vast range of topics, from love to religion to happiness. Considered a pioneer of “radical-humanistic psychoanalysis,” he was a leading intellectual of the twentieth century. However, like many impactful figures, Fromm possessed both remarkable talents and significant blind spots. Throughout his creative life, he grappled with balancing periods of exuberance with depressive moods.

The renowned German psychologist and philosopher, Erich Fromm (March 23, 1900–March 18, 1980), explored a vast range of topics, from love to religion to happiness. Considered a pioneer of “radical-humanistic psychoanalysis,” he was a leading intellectual of the twentieth century. However, like many impactful figures, Fromm possessed both remarkable talents and significant blind spots. Throughout his creative life, he grappled with balancing periods of exuberance with depressive moods.

To address these struggles, he developed a framework for mental well-being, consisting of four pillars of mental health. Lawrence J. Friedman delves into this aspect of Fromm’s life in his book, The Lives of Erich Fromm: Love’s Prophet. Friedman begins by describing Fromm’s emotional “triangle” – a concept encompassing exuberance, depression, and marginality.

Lawrence J. Friedman writes:

The first corner, exuberance, consisted of what clinicians too readily label “hypomania” — a state of boundless energy, reduced self-governance, and socially inappropriate words and deeds. This diagnosis falls short in understanding Fromm. His exuberance reflected an exceedingly joyous but hardly a precarious temperament. Boundless happiness and delight was evident at many of his parties, which revolved around stimulating discussions, gourmet food, and a limitless supply of jokes and good wine. … In one of his letters, Fromm told (his third wife) Annis that a life well lived was an exuberant state of existence where prudence sometimes had to be cast aside. … While it is not helpful to tag Fromm’s feelings and behaviors in these instances as hypomanic, he certainly seemed at times to show a vaguely manic disposition.

But this state of boundless happiness had an opposite:

The second corner of Fromm’s emotional triangle was represented by a depressive mood that was also characteristic of his mother’s. The suicides that punctuated his life weighed heavily on Fromm, from the early death of a promising young woman painter through the self-inflicted deaths of several of his patients to the ultimate personal pain of his second wife’s passing. Major illnesses throughout his life were also dispiriting, and by the early 1960s, Fromm’s certainty that there would be a global nuclear war caused him tremendous despair.

Friedman goes on to describe the third element of Fromm’s emotional life:

A state of marginality occupied the third corner of the internal triangle. Whereas extreme exuberance and depression are often unique to an individual and carry a heavy genetic component, marginality and estrangement derive to a large extent from social situations. Fromm felt estranged from his family as his parents clung emotionally to him to mitigate a miserable marriage. In the late 1930s, Fromm felt rejected and bitter when he was fired from the Frankfurt Institute. The feeling recurred when he was ousted not only from orthodox psychoanalytic societies but from societies run by neo-Freudians. In these situations, Fromm saw himself on the sidelines in a world where consumerism and warrior virtues were in vogue.

Friedman continues by writing that Fromm’s triangular emotional life was far from stable:

On a given day, he could feel depressed and marginalized. On another day, a sense of exuberance might be reduced by the feelings of estrangement. Once in a while, however, these unpredictable interactions worked out well — and always when he dined with Riesman or Fulbright or spent time with Annis.

Friedman notes that when Fromm felt distressed or downcast, he could rely on four “stabilizers” or pillars of mental health he had built along the outskirts of the emotional triangle, first of which was his daily routine:

First, he maintained a regular, predictable daily schedule. As he wrote to Lewis Mumford, “I actually live pretty much the same way I used to live.” He started every day by walking for thirty minutes, writing for four hours, then meditating for an hour. He had a quick lunch and spent afternoons in a varied allotment of tasks — clinical work with his patients, reviewing materials relevant to his writing projects, and dictating letters.

The second one was his writing projects:

Second, but also illustrative of his efforts to retain equanimity, Fromm progressed energetically on each of his writing projects once he decided his approach to the topic. He began each new book or article by locating what Freud and, to a lesser degree, Marx had written about the topic. Next, he reviewed and incorporated what he had already written about the topic. Fromm was often self-referential. Drawing more from his earlier formulations than from the feedback of thoughtful critics or new evidence, he could write quickly but was necessarily limited in depth and nuance. … Fromm usually structured his writing around binaries — freedom and authoritarianism, love and hate, biophilia and necrophilia, “having” consumer items or “being” a productive self. In some measure, he was pursuing the teaching of D.T. Suzuki, his sometime mentor. In his variation of Zen Buddhism, Suzuki postulated that thinking was dualistic — dividing all phenomena into opposites.

The third one was his friends and colleagues:

Third, Fromm would always seek out convivial groups of intellectuals and artists that in some ways resembled Mable Dodge Luhan’s assemblage in Taos. These, too, were stabilizers, providing him with comfort and perhaps a bit of humor, a lively and supportive social life, and a helpful forum in which to test out new concepts, intuitions, and clinical perspectives. He referred to these groups as “humanistic” collectivities. … During Fromm’s years in Locarno he participated in a group that … discussed Buddhism, the problems of Israel as a Jewish state, and Fromm’s latest binaries — Having and Being. He thrived in these groups of convivial and thoughtful colleagues.

The fourth one was spirituality:

Spirituality, the fourth stabilizer, was perhaps the most important. Fromm’s embrace of spirituality derived from his exposure to prophetic Judaism, Christian mysticism, and Zen Buddhism. He considered spirituality to be something within the self but also beyond both the self and the society. Yet it did not require the premise that a God existed. For Fromm, the nature and depth of one’s spirituality governed one’s entire orientation toward the world, shaping personal conduct and relationships. Fromm’s spirituality affixed itself to his prophetic disposition, energizing his prophetic call for freedom, justice, and the love of life. Most important, it was a plea from the heart. Fromm found the most intense and fundamental form of spirituality in the unconditional love of a mother for her newborn. The task at hand was to extend that spirituality to all human relationships.

Friedman concludes with this touching sentiment:

Fromm once acknowledged that through stabilizers, “I’ve done what I could to repair that damage” of his parental household. If not for these grounding elements, his creative and scholarly productivity and his political activity would have been negligible. We might never have heard of Erich Fromm. Fromm was his own best clinician.

Complement The Lives of Erich Fromm, a contemplative read in its entirety, with a rare Erich Fromm Mike Wallace interview.

I’m a freelance writer with 6 years of experience in SEO blogging and article publishing. I currently run two websites: MindfulSpot.com and OurReadingLife.com. While you’re here, get the latest updates by subscribing to my newsletter.