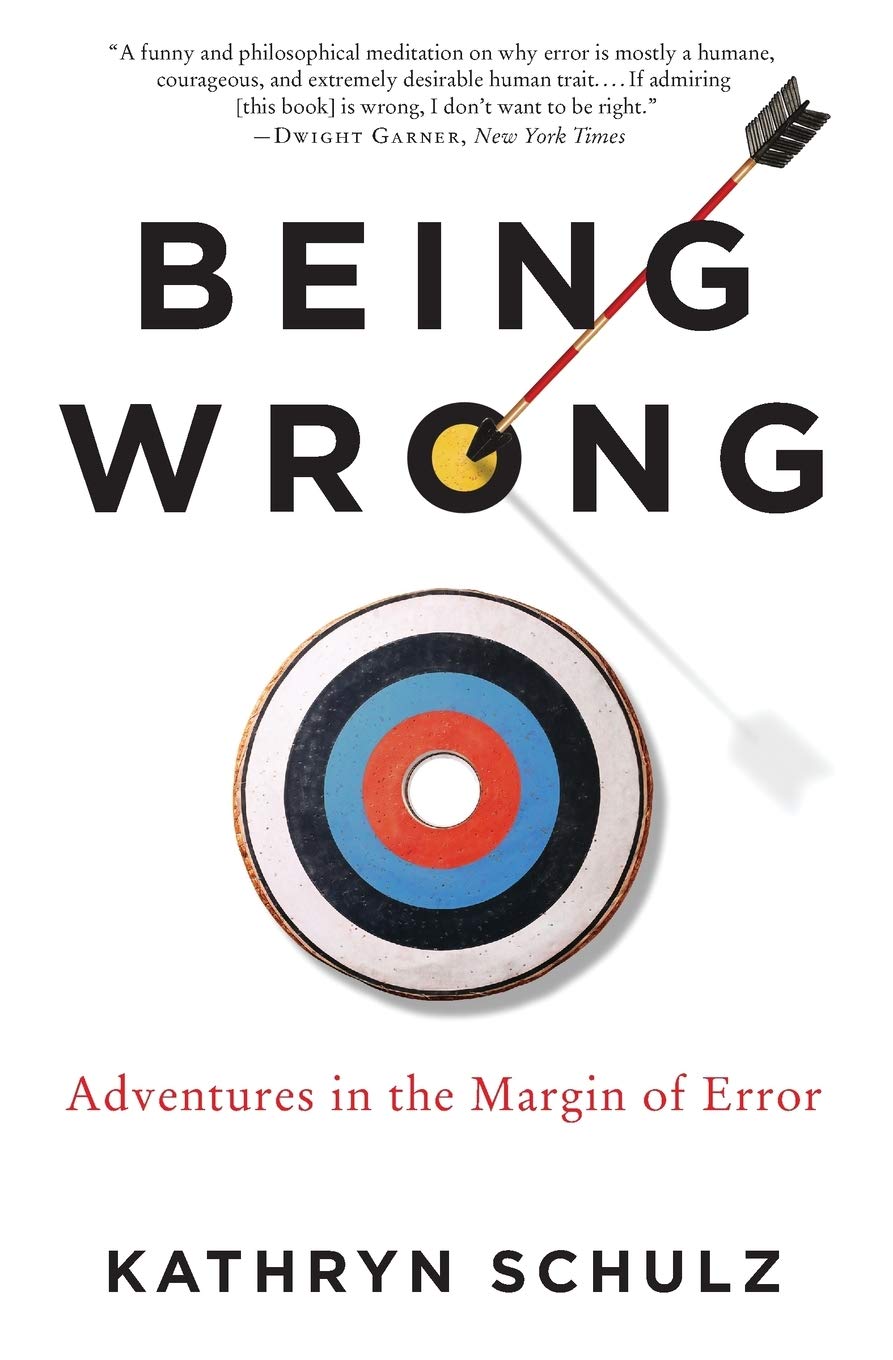

You are wrong. I am wrong. From time to time, everyone is wrong about something or someone — and completely unaware of it. But wrongness, as it turns out, is not what you think it is. “Wrongness is a window into normal human nature — into our imaginative minds, our boundless faculties, our extravagant souls,” writes Pulitzer-winning writer Kathryn Schulz in her book Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error. “However disorienting, difficult, or humbling our mistakes might be, it is ultimately wrongness, not rightness, that can teach us who we are.”

You are wrong. I am wrong. From time to time, everyone is wrong about something or someone — and completely unaware of it. But wrongness, as it turns out, is not what you think it is. “Wrongness is a window into normal human nature — into our imaginative minds, our boundless faculties, our extravagant souls,” writes Pulitzer-winning writer Kathryn Schulz in her book Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error. “However disorienting, difficult, or humbling our mistakes might be, it is ultimately wrongness, not rightness, that can teach us who we are.”

It may be uncomfortable, but embracing the joy of being wrong — about yourself and, more importantly, about other people — can be a tool of inner growth. And it can also be a vital spiritual practice that can heal our fractured world. But to integrate it into our daily lives, we need to understand how we are wrong about being wrong. Kathryn Schulz writes:

A whole lot of us go through life assuming that we are right, all the time, about everything: about our political and intellectual convictions, our religious and moral beliefs, our assessment of other people, our memories, our grasp of facts. As absurd as it sounds when we stop to think about it, our steady state seems to be one of unconsciously assuming that we are very close to omniscient.

[…]

If we relish being right and regard it as our natural state, you can imagine how we feel about being wrong. For one thing, we tend to view it as rare and bizarre — an inexplicable aberration in the normal order of things. For another, it leaves us feeling ashamed. Like the term paper returned to us covered in red ink, being wrong makes us slouch down in our seat; it makes our heart sink and our dander rise. At best we regard it as a nuisance, at worst a nightmare, but in either case we experience our errors as deflating and embarrassing.

[…]

Of all the thing we are wrong about, this idea of error might well top the list. It is our meta-mistake: we are wrong about what it means to be wrong. Far from being a sign of intellectual inferiority, the capacity to err is crucial to human cognition. Far from being a moral flaw, it is inextricable from some of our most humane and honorable qualities: empathy, optimism, imagination, conviction, and courage. And far from being a mark of indifference or intolerance, wrongness is a vital part of how we learn and change.

By examining our sense of certainty and our reaction to error, Schulz argues, we can learn to think differently about our convictions, especially in those situations where the line between right and wrong becomes blurry if not completely invisible. The relationship we cultivate with our errors affects how we think about and treat our fellow human beings — and this is the essence of ethics. Kathryn Schulz writes:

Do we have an obligation to others to contemplate the possibility that we are wrong? What responsibility do we bear for the consequences of our mistakes? How should we behave toward people when we think that they are wrong? The writer and philosopher Iris Murdoch once observed that no system of ethics can be complete without a mechanism for bringing about moral change. We don’t usually think of mistakes as a means to an end, let alone a positive end — and yet, depending on how we answer these questions, error has the potential to be just such a mechanism. In other words, erring is not only (although it is sometimes) a moral problem. It is also a moral solution: an opportunity to rethink our relationship to ourselves, other people, and the world.

Noting that being wrong “can be shocking, confusing, funny, embarrassing, traumatic, pleasurable, illuminating, and life-altering” experience, Katherine Schulz pinpoints a crucial difference between this point of realization and the feeling of being wrong prior to it:

By definition, there can’t be any particular feeling associated with simply being wrong. Indeed, the whole reason it’s possible to be wrong is that, while it is happening, you are oblivious to it. When you are simply going about your business in a state you will later decide was delusional, you have no idea of it whatsoever. … So I should revise myself: it does feel like something to be wrong. It feels like being right.

She goes on to note how this paradox makes it impossible for us to speak about being wrong in the first person present tense:

This is the problem of error-blindness. Whatever falsehoods each of us currently believes are necessarily invisible to us. Think about the telling fact that error literally doesn’t exist in the first person present tense: the sentence “I am wrong” describes a logical impossibility. As soon as we know that we are wrong, we aren’t wrong anymore, since to recognize a belief as false is to stop believing it. Thus we can only say “I was wrong.” … We can be wrong, or we can know it, but we can’t do both at the same time.

Yet, Kathryn Schulz notes, if we find this mental trickery troubling, we should also find it comforting:

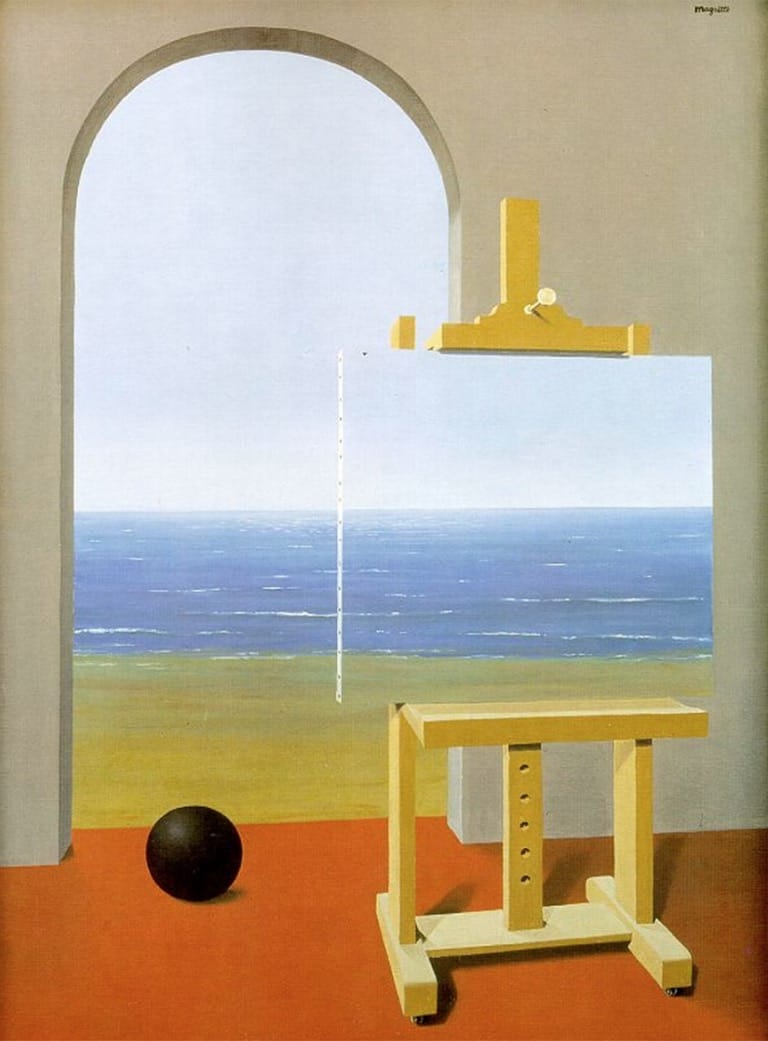

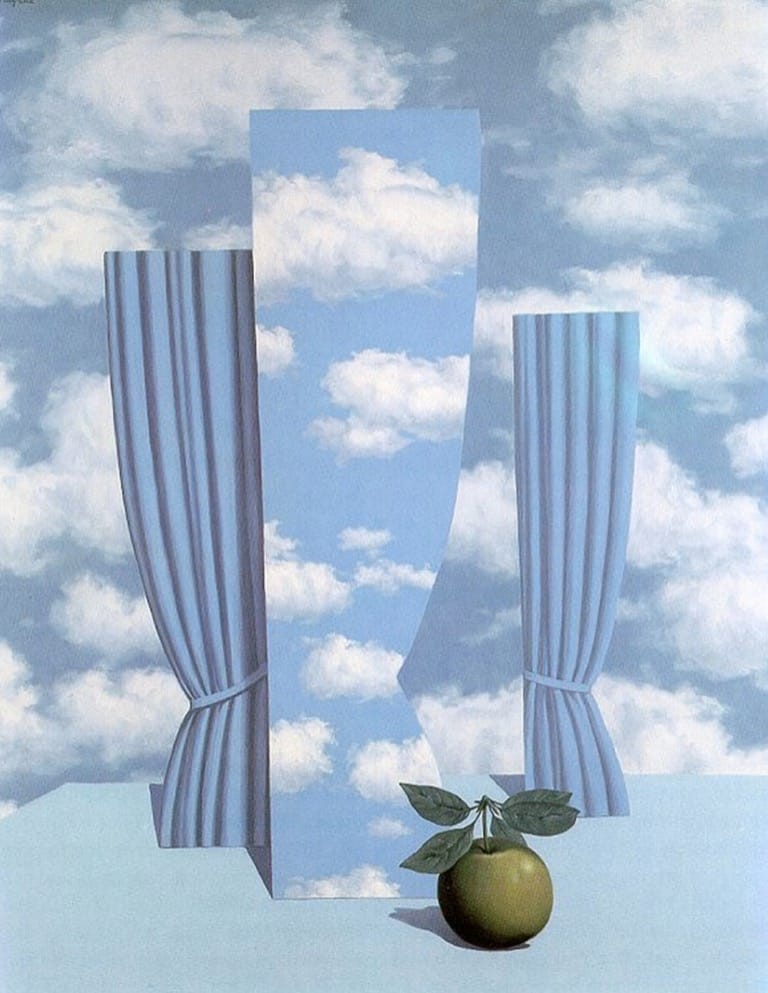

The miracle of the human mind, after all, is that it can show us the world not only as it is, but also as it is not: as we remember it from the past, as we hope or fear it will be in the future, as we imagine it might be in some other place or for some other person. … “Seeing the world as it is not” is pretty much the definition of erring — but it is also the essence of imagination, invention, and hope. As that suggests, our errors sometimes bear far sweeter fruits than the failure and shame we associate with them. True, they represent a moment of alienation, both from ourselves and from a previously convincing vision of the world. But what’s wrong with that? “To alienate” means to make unfamiliar; and to see things — including ourselves — as unfamiliar is an opportunity to see them anew.

Complement Being Wrong — one of the most important secular spiritual books of our time — with the video below which shows us the benefits of challenging our beliefs, opening up to other worldviews, and becoming more open to other people:

I’m a freelance writer with 6 years of experience in SEO blogging and article publishing. While you’re here, get the latest updates by subscribing to my newsletter.