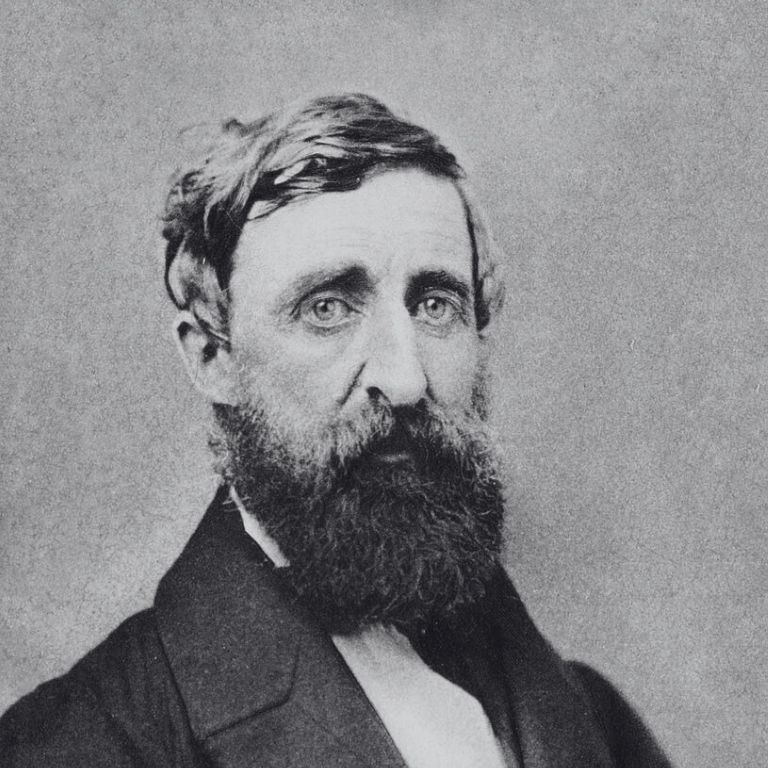

In 1845, moved by the desire to reconnect with the essence of his own being, great Transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817–May 6, 1862) embarked on a voluntary two-year exile in the woods, an experiment in simple living and contemplation of nature, which later became the basis for his book Walden; or, Life in the Woods. This is what he noted in one of his journal entries, “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

In 1845, moved by the desire to reconnect with the essence of his own being, great Transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817–May 6, 1862) embarked on a voluntary two-year exile in the woods, an experiment in simple living and contemplation of nature, which later became the basis for his book Walden; or, Life in the Woods. This is what he noted in one of his journal entries, “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

But the transition was not as smooth as he expected. About a few weeks after he came to the woods, and only for an hour, he doubted if the near neighborhood of man was not essential to a serene and healthy life. At the same time, he was aware of a slight insanity in his mood and foresaw a quick recovery. Thoreau writes:

Yet I experienced sometimes that the most sweet and tender, the most innocent and encouraging society may be found in any natural object, even for the poor misanthrope and most melancholy man. There can be no very black melancholy to him who lives in the midst of Nature and has his senses still. There was never yet such a storm but Aeolian music to a healthy and innocent ear. Nothing can rightly compel a simple and brave man to a vulgar sadness. While I enjoy the friendship of seasons I trust that nothing can make a life a burden to me.

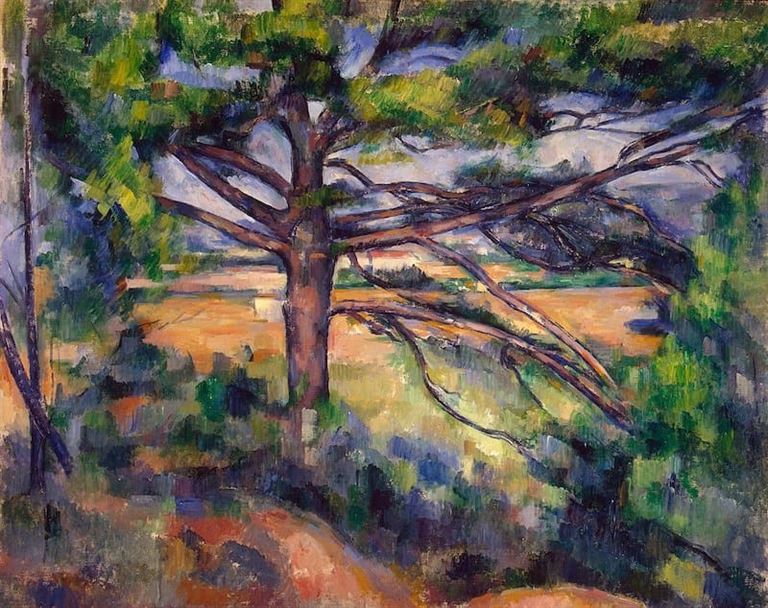

What he lacked in human company, he made up in excess by observing the natural phenomena around him:

Every little pine needle expanded and swelled with sympathy and befriended me. I was so distinctly made aware of the presence of something kindred to me, even in the scenes which we are accustomed to call wild and dreary, and also the nearest of blood to me and humanest was not a person nor a villager, that I thought no place could ever be strange to me again.

When he did meet someone from the nearby village, they often said to him, “I should think you would feel lonesome down there, and want to be nearer to folks, rainy and snowy days and nights especially.” To which he replied:

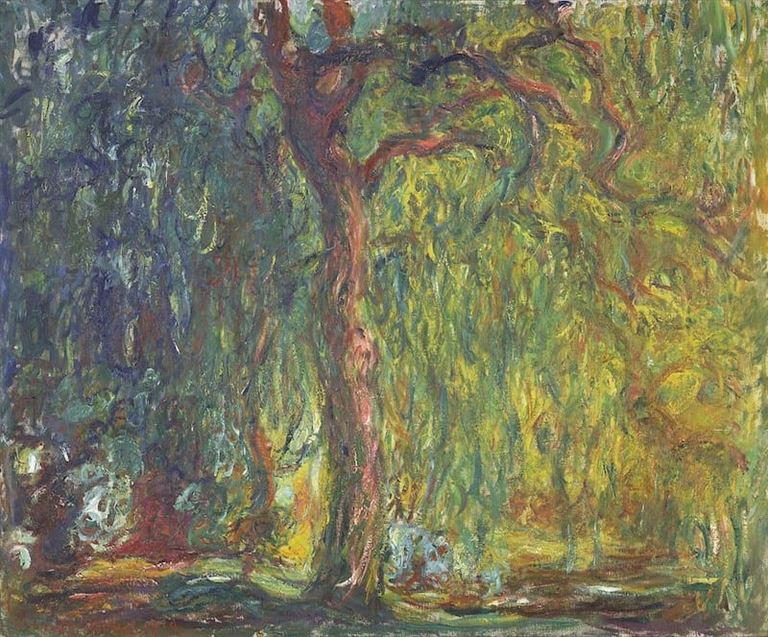

What sort of space is that which separates a man from his fellows and makes him solitary? I have found that no exertion of the legs can bring two minds much nearer to one another. What do we want most to dwell near to? Not to many men surely, the depot, the post-office, the bar-room, the meeting-house, the school-house, the grocery, Beacon Hill, or the Five Points, where men most congregate, but to the perennial source of our life, whence in all our experience we have found that to issue, as the willow stands near the water and sends out its roots in that direction. This will vary with different natures, but this is the place where a wise man will dig his cellar.

Then towards the end of the chapter he writes:

The indescribable innocence and beneficence of Nature, — of sun and wind and rain, of summer and winter, — such health, such cheer, they afford forever! and such sympathy have they ever with our race, that all Nature would be affected, and the sun’s brightness fade, and the winds would sigh humanely, and the clouds rain tears, and the woods shed their leaves and put on mourning in midsummer, if any man should ever for a just cause grieve. Shall I not have intelligence with the earth? Am I not partly leaves and vegetable mould myself?

Walden; Or Life in the Woods is one of the best books about finding healing solitude in nature. Complement with Wendell Berry on what is good for the world and then revisit deep ecologist John Seed on going beyond anthropocentrism.

I’m a freelance writer with 6 years of experience in SEO blogging and article publishing. I currently run two websites: MindfulSpot.com and OurReadingLife.com. While you’re here, get the latest updates by subscribing to my newsletter.