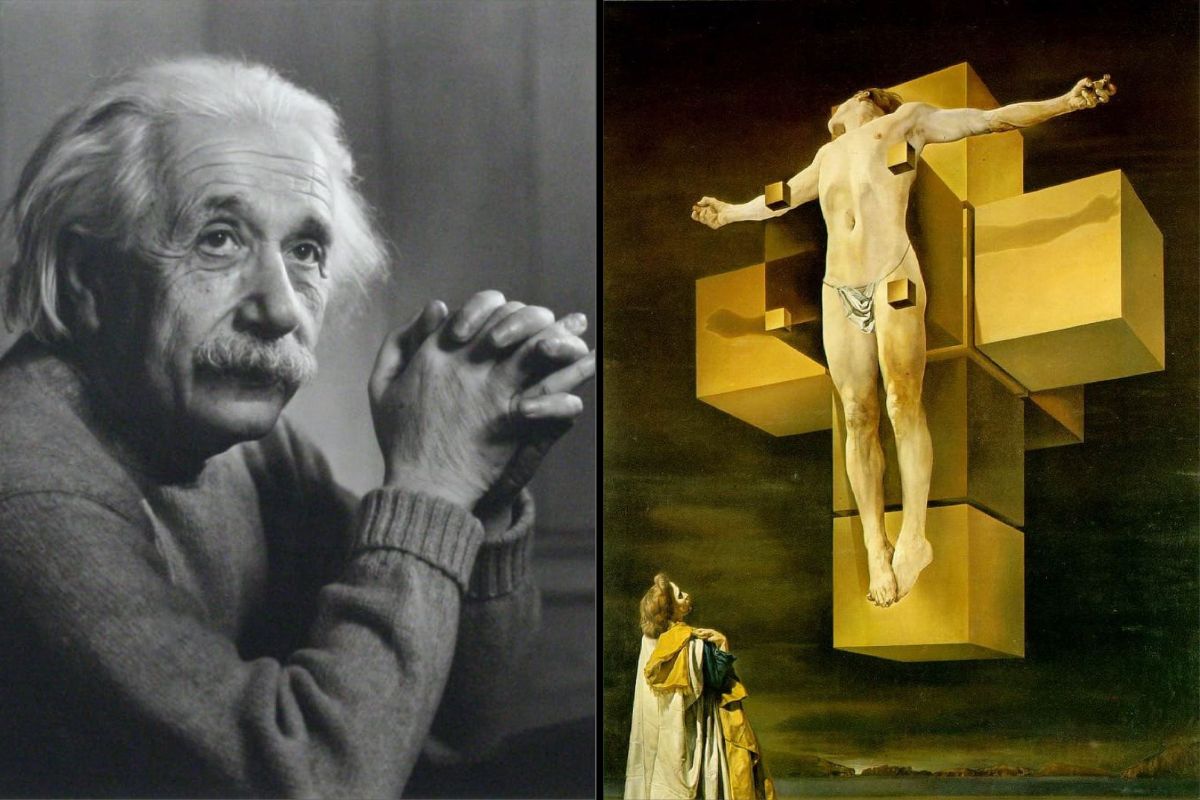

“A human being is a part of the whole, called by us ‘Universe,’ a part limited in time and space,” Albert Einstein wrote in a beautiful letter of consolation to a grieving father. “He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest—a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. The striving to free oneself from this delusion is the one issue of true religion. Not to nourish the delusion but to try to overcome it is the way to reach the attainable measure of peace of mind.”

“A human being is a part of the whole, called by us ‘Universe,’ a part limited in time and space,” Albert Einstein wrote in a beautiful letter of consolation to a grieving father. “He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest—a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. The striving to free oneself from this delusion is the one issue of true religion. Not to nourish the delusion but to try to overcome it is the way to reach the attainable measure of peace of mind.”

If this letter was anonymous and we knew nothing about the sender, how would we describe the person? A contemplative? A sage? An enlightened being? These are the words that come to mind when we read these truly profound lines that capture fundamental truths of our existence. What doesn’t come to mind are words such as scientist, mathematician, or theoretical physicist. For many of us, it feels almost impossible to speak of spirituality and science in the same frame of mind. We consider these two spheres of our lives irreconcilable and opposite each other. Albert Einstein (March 14, 1879–April 18, 1955) was himself aware of this widespread and persisting dichotomy, and that is why he addressed it in his essay titled “Science and Religion,” included in an altogether indispensable Out of My Later Years. He writes:

It is true that convictions can best be supported with experience and clear thinking. On this point one must agree unreservedly with the extreme rationalist. The weak point of his conception is, however, this, that those convictions which are necessary and determinant for our conduct and judgments, cannot be found solely along this solid scientific way. For the scientific method can teach us nothing else beyond how facts are related to, and conditioned by, each other. The aspiration toward such objective knowledge belongs to the highest of which man is capable…. Yet it is equally clear that knowledge of what is does not open the door directly to what should be. One can have the clearest and most complete knowledge of what is, and yet not be able to deduct from that what should be the goal of our human aspirations.

Following this train of thought, Einstein notes that, indeed, objective knowledge can serve as a way to achieve certain ends, but the ultimate goal itself and the longing to reach it must come from another source:

When someone realizes that for the achievement of an end certain means would be useful, the means itself becomes thereby an end. Intelligence makes clear to us the interrelation of means and ends. But mere thinking cannot give us a sense of the ultimate and fundamental ends. To make clear these fundamental ends and valuations, and to set them fast in the emotional life of the individual, seems to me precisely the most important function which religion has to perform in the social life of man. And if one asks whence derives the authority of such fundamental ends, since they cannot be stated and justified merely by reason, one can only answer: they exist in a healthy society as powerful traditions, which act upon the conduct and aspirations and judgments of the individuals; they are there, that is, as something living, without its being necessary to find justification for their existence.

With this, Einstein turns to the essential qualities of the religious person:

A person who is religiously enlightened appears to me to be one who has, to the best of his ability, liberated himself from the fetters of his selfish desires and is preoccupied with thoughts, feelings, and aspirations to which he clings because of their super-personal value. it seems to me that what is important is the force of this super-personal content and the depth of the conviction concerning its overpowering meaningfulness, regardless of whether any attempt is made to unite this content with a divine Being, for otherwise it would not be possible to count Buddha and Spinoza as religious personalities. Accordingly, a religious person is devout in the sense that he has no doubt of the significance and loftiness of those super-personal objects and goals which neither require nor are capable of rational foundation. They exist with the same necessity and matter-of-factness as he himself. In this sense religion is the age-old endeavor of mankind to become clearly and completely conscious of these values and goals and constantly to strengthen and extend their effect.

The dichotomy of “Science and Religion,” an integral part of Einstein’s Out of My Later Years, remains an enduring guide for reconciling the inner conflicts of our minds. Complement with Einstein’s letter to a grieving father.